For students on the MA in Fine and Decorative Art and Design, a visit to Hampstead’s iconic Isokon Flats offers more than a glimpse of architectural history—it opens a window onto a pivotal moment in modernism. In the 1930s, this quiet corner of north London became a vibrant hub for artists, architects, and intellectuals fleeing political unrest in Europe.

In the late 1930s, you could walk from Sigmund Freud’s home to Piet Mondrian’s in a little over twenty minutes—but you wouldn’t be in Paris, New York, or Vienna. Along the way, you could pass by the modernist flats that had, until recently, housed the Bauhaus masters Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and László Moholy-Nagy, but you wouldn’t be in Germany or the United States. While the nearby residences of Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Ben Nicholson might help place the setting, you wouldn’t be in central London either. This is Hampstead—London’s unlikely but thriving hub of modernism. All of these figures play a role in our students learning about modern art and design on the MA Fine and Decorative Art and Design program.

Situated on a hill to the north of the city, Hampstead was, at first glance, an unexpected stage for a modernist revolution. In the late 19th century, figures like James Whistler and his followers gravitated toward Chelsea by the Thames, while the Bloomsbury Group, closely associated with the British Museum and Sotheby’s Institute of Art, gathered in central London.

These neighborhoods boasted art schools and galleries. Hampstead had neither—but it did offer large, relatively affordable houses, a green, village-like atmosphere, the sweeping views of Hampstead Heath, and a railway network, now part of the Northern Line, that got you back into central London quickly.

It soon began to attract writers like George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh, along with British artists such as the surrealist Roland Penrose, who penned the first English-language biography of Pablo Picasso and later married the photographer Lee Miller.

Once these residents reached critical mass, Hampstead became a natural destination for those seeking to escape the rise of Nazism from 1933. Over the next decade or so, an astonishing roster of artists, architects, and writers lived there. The Dada photomontager John Heartfield, Russian Constructivist Naum Gabo, crime writer Agatha Christie, art critic and friend of Peggy Guggenheim Herbert Read, architect and designer of the Penguin Pool at London Zoo Berthold Lubetkin, and photographer and spy Edith Tudor-Hart were just some of the names added to those above.

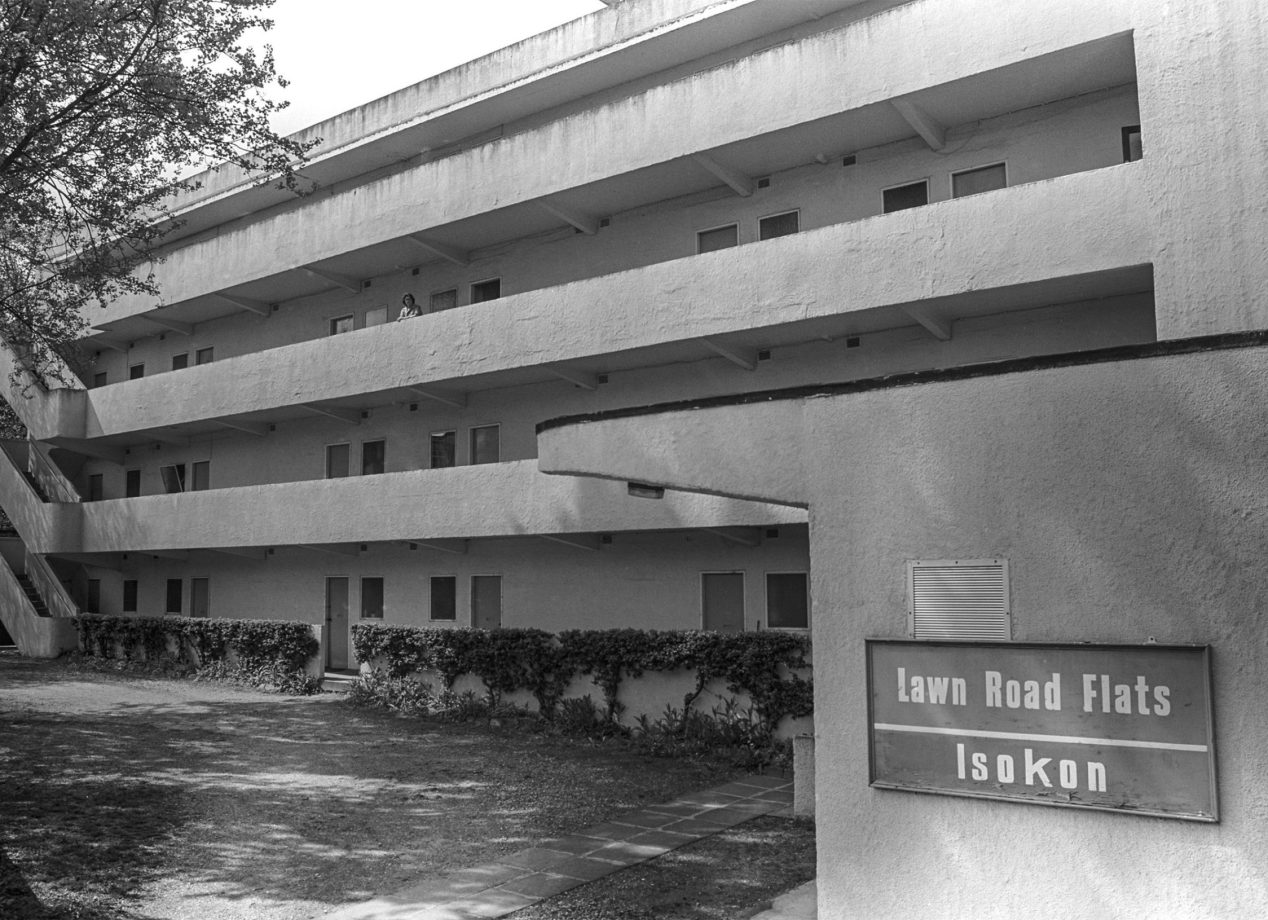

These émigrés brought with them radical ideas from de Stijl and the Bauhaus, which found fertile ground among the British modernist community already established in Hampstead. One lasting legacy of this cultural exchange is the Lawn Road Flats, also known as the Isokon Flats—a modernist apartment block that forms a core part of the learning experience for students on the MA in Fine and Decorative Art and Design.

Isokon was founded by Jack and Molly Pritchard. Since the 1920s, Jack had worked importing plywood, the modern material that Alvar Alto was using for his furniture. Recruiting the Canadian architect and designer Wells Coates, they formed Isokon to build 32 modernist flats in reinforced concrete. One of the highlights of the academic year is standing in the penthouse flat where Molly and Jack made their home, thanks to the doors opened by Leyla Daybelge, an alumna of Sotheby’s Institute and co-author, with Magnus Englund, of Isokon and the Bauhaus in Britain, the definitive history of the company. She refers to the Flats, opened in 1934, as the “ground zero of modernist apartment living” in Britain.

Soon after they opened, former Bauhaus Director Gropius came to live there, bringing with him Breuer and Moholy-Nagy. Breuer began to work for the company, designing the Isokon Long Chair in bent plywood and the Isobar, the social centre of the Isokon Flats, a club where residents and members could enjoy fine dining courtesy of Philip Harden, Britain’s first television chef. The history of Isokon is so compelling that some of our students have volunteered at the gallery the Isokon Gallery Trust runs in what was once the Isobar. Moholy-Nagy produced adverts for Isokon alongside graphic work for other high-tech companies such as London Underground and Imperial Airlines. He also designed the shop windows for a menswear store opposite the Royal Academy, currently Waterstone’s bookshop Piccadilly.

Beyond the Flats, students on the MA in Fine and Decorative Art and Design program also explore nearby modernist landmarks, including the Sun House by Maxwell Fry, and 2 Willow Road, designed by Ernő Goldfinger. The latter was the first modernist home acquired by the National Trust, and its owner—whose name famously inspired Ian Fleming’s villain—amassed an important art collection including works by Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, and Bridget Riley.

Goldfinger stayed, designing the famous post-war London landmarks of Trellick and Balfron Towers, divisive Brutalist masterpieces in West and East London. The Bauhaus contingent, however, were lured away to the United States, Gropius to a position at Harvard, Moholy-Nagy to found the New Bauhaus in Chicago and Breuer to realise his architectural ambitions, most notably by designing the Whitney Museum of American Art, now known as the Breuer Building, which, fittingly, will shortly become Sotheby’s New York headquarters.

Photo credit: Steve Cadman, Isokon Building, London (2007), via Wikimedia Commons.

Ready to hone your visual, critical, and research skills through an integrated study of fine art, decorative art, and design? Explore this graduate program.